- Interview with Dr. Sarwar Abdulrahman regarding the strikers

- Press Conference in Support of Striking Teachers

- Press Conference of the Islamic Union Faction on the Parliament Session

- Press Conference of the New Generation Faction in the Kurdistan Parliament

- The Kurdistan Parliament Did Not Release Any Statement About Today’s Session

- Mohammed Suleiman Steps Down as Acting Speaker; Azad Mohammed Becomes Acting Speaker of the Kurdistan Parliament

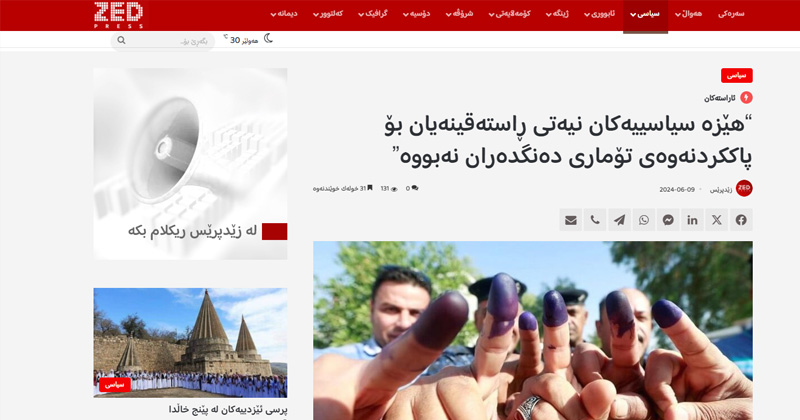

Political Parties Had No Genuine Intention to Clean the Voter Registry

The complications surrounding the "Voter Registry" have intensified, leading to a situation where the registry has always been manipulated by political forces and used as a pretext for postponing elections.

For ongoing news and information, follow ZedPress on Telegram.

In this context, the report by the PAY Foundation clarifies that, over the past several years, despite the voter registry in the Kurdistan Region being neither cleaned nor trustworthy, the political parties have generally lacked a sincere intention to rectify and organize the voter list. This is because they have benefited from the inconsistencies within the registry and used the absence of a clean list as an excuse to manipulate elections.

Below is the section of the PAY Foundation’s report that discusses the state of the voter registry in the Kurdistan Region:

State of the Voter Registry in the Kurdistan Region

One of the key pillars of any free and fair election is the existence of a reliable voter registry that accurately records the data of voters, including their names, family names, mother's name, birth history, and residence. Without such a registry, elections cannot be considered free and democratic. Therefore, citizens must be able to register their names equally and according to established procedures and international standards, allowing them to participate in elections, as outlined in international human rights charters, civil and political rights conventions, and the international standards for free and fair elections that prohibit discrimination.

At the same time, citizens must be protected from being excluded from participation in elections due to any barriers to registering their names.

In previous elections in the Kurdistan Region, the voter registry has consistently been a point of contention among political entities, serving as a source of disagreement and mistrust because it has never met the demands and standards expected by political parties. The voter list has always been a tool exploited by political forces, used as a justification to delay elections.

Historical Overview of the Voter Registry in the Kurdistan Region

The first parliamentary election was held on May 19, 1992, conducted by the Kurdistan Front under Law No. 1 of 1992. According to this law, "every citizen of the Kurdistan Region had the right to vote if they were an Iraqi Kurdistan citizen aged 18 and above."

Since no official voter registry existed at that time, every citizen who met the legal requirements could vote at polling stations. To prevent double voting and fraud, voters' fingers were marked with ink, and their civil status records (Ahwal Madani) were reviewed to ensure they did not vote more than once. Despite these precautions, fraud occurred, and political parties accused each other of irregularities, with evidence presented against each other.

The second election was held on January 30, 2005, simultaneously with the elections for the Iraqi Council of Representatives and the provincial councils. This was the first general election after the fall of the Baath regime in Kurdistan and Iraq. In this election, the residents of Kurdistan voted separately for three different councils: the Kurdistan Parliament, held in the provinces of Sulaymaniyah, Erbil, and Dohuk; the Iraqi Council of Representatives; and the provincial councils.

This election was conducted using a proportional representation system, with 2,290,736 eligible voters in the Kurdistan Region, of whom 1,753,919 participated in the process, representing 75.6% of the region’s population.

Investigation Committee in the Third Term of the Kurdistan Parliament

In the elections of the third term, held on July 25, 2009, this term was distinct because the opposition emerged and entered the parliament. There were 2,401,795 eligible voters in the region, of whom 1,876,196 participated, representing 78.1% of the voters.

Due to suspicions by political parties about the voter registry, including many fake names, parliament members submitted a request signed by 39 members to the presidency of the parliament, asking for the registry to be cleaned. As a result, in July 2013, Parliament decided to form a committee consisting of representatives from various factions to investigate this matter. After two months of work and meetings with related parties, including the High Electoral Commission, ministries, and other bodies, the committee reported that the registry contained hundreds of thousands of fake, duplicate, and deceased names, recommending that it be cleaned. However, due to the political situation and conflicts among political parties, the parliamentary presidency did not act on the committee's recommendations, and the report was ignored.

As a result, the elections for the fourth parliamentary term were conducted with the same flawed registry, filled with irregularities. Both political parties and civil society organizations monitoring the elections acknowledged the voter registry as a significant source of fraud.

Key Issues with the Voter Registry in the Kurdistan Region:

No accurate census exists, and it is unknown how many residents of the region are eligible to vote. Different figures are often cited.

The voter registry was established based on outdated data from 1996, and many deceased individuals since then remain listed.

Those who had relocated back to areas like Kirkuk, Mosul, Salahaddin, Diyala, and Makhmur, due to Article 140 measures, still have their names in the Kurdistan Region's voter registry.

Numerous duplicate and multiple entries exist within the registry.

Some residents from Turkish, Syrian, and Iranian Kurdistan with residency permits have fraudulently obtained Iraqi ID cards and are listed in the registry.

Security forces and Peshmerga members are often listed twice, both in special lists and the general voter registry, allowing them to vote twice.

Responsibility and Inaction:

The Independent High Electoral and Referendum Commission of the region, which should function independently and be accountable to the parliament, failed to fulfill its duties. Neither the parliament nor the political parties took adequate action to clean the registry despite being aware of the fraudulent entries.

Although the third term parliament formed a committee to address the issue, the fourth and fifth terms failed to take any concrete steps, and political parties continued to use the flawed registry to their advantage, often as an excuse to delay elections.

The political parties and parliament's lack of genuine effort to clean the voter registry reflects a broader reluctance, as the flawed registry serves as a convenient excuse to manipulate election timings and outcomes.

The stance of political parties on not cleaning the voter registry can be attributed to several reasons:

Some of the dominant political parties may find this irregularity, and the presence of many fake, deceased, and duplicate names in the voter registry, beneficial and use it during elections.

Cleaning the voter registry requires timely action; however, they haven’t worked on it in normal times, and now, by arguing to delay the elections to avoid backlash, some parties are engaging in some kind of political bargaining as if they’re pretending to allow the elections to be postponed.

Other than these points, there is no logical reason that any political party would not adopt a stance on the issue. This occurs at a time when they agreed to elections with this voter registry, essentially legalizing electoral fraud, with the blame falling on all those parties that agreed and upheld this flawed, corrupt voter list as the foundation for the region’s political system and institutions.

If there were no benefits, then why did the parties in the third parliamentary term (2013) create a parliamentary committee for this issue, and the committee’s decisions and recommendations in the form of a report were sent to the parliamentary presidency, which was under the control of the KDP and the PUK? Neither party was ready to hold a parliamentary session on it and put the report to a vote! If this wasn’t the case, why did the opposition parties like Gorran, Komal, and the Islamic Union remain silent and take no stance on all these corruptions of the voter registry?

If there were no benefits, why did neither the fourth nor the fifth parliamentary terms, which spanned ten years, have any parliamentary presidencies or factions that took steps to clean the voter registry, nor did they send any formal request to the responsible bodies?

If there were no benefits, why did all these parties, which participated in the government during the eighth cabinet, and the KDP, PUK, and Gorran during the ninth cabinet, not fulfill this responsibility?

If there were no benefits and the parties are not neglectful, then why do all five parties (KDP, PUK, Gorran, Komal, and the Islamic Union) have representatives on the commission, and the commission is not independent, but independent in name only! Which day did they call on their representatives on the commission to clean the voter registry and exert pressure through their own mechanisms? For example, the critique against the commission's impartiality has never been the issue that the parties themselves, through their cadres, bear the responsibility of conducting clean elections! Undoubtedly, the burden of this illegal situation rests with all five parties according to their weight and none of them is without blame.

To reiterate, over the past ten years, we, as the Pay Organization, have sent numerous reports and notices to the Presidency, Parliament, and political parties. We even officially met with the Electoral and Referendum Commission and submitted formal complaints regarding the registry, with documents and evidence provided to them. In addition to these, we organized several conferences, workshops, and meetings attended by relevant parties, but all went unanswered. Neither the parties paid attention nor did Parliament, the commission, or other related entities take any action.

The Aftermath of the Federal Court Decision and the Future of Elections

The election for the sixth term of the Kurdistan Parliament was supposed to be held on October 1, 2022. However, due to disagreements between the KDP and the PUK over how to amend the election law and activate the Kurdistan Election and Referendum Commission, the election was postponed.

After postponing the election from its original date, President Nechirvan Barzani issued a decree to extend the election period and set a new date for October 9, 2022, after issuing a decree in March 2023. From March until October, political parties, especially the KDP and the PUK, held several meetings at the Presidency of the Region to reach an agreement on holding the elections but failed to achieve any results.

One of the main points of disagreement between the KDP and PUK was over the seats allocated to minorities (quota). From the beginning of the negotiations, the PUK demanded that the Kurdistan elections be held similar to the Iraqi parliamentary elections of 2021 with an open constituency system because the PUK and other parties believed that the single constituency system had allowed the KDP to gain a majority of seats, whereas the open constituency system would distribute votes more equitably and reduce the KDP’s parliamentary majority. The KDP accepted this demand, but concurrently with the multi-constituency system, the PUK demanded that the quota seats be distributed among the constituencies, particularly allocating (2 to 4) of the (11) quota seats to the Sulaymaniyah governorate. The KDP did not agree to this demand, which led to the postponement of the election and the annulment of Barzani's first decree.

Due to the failure of negotiations, President Nechirvan Barzani was compelled to issue a second decree on October 18, 2023, for the holding of elections. However, the disagreement between the KDP and PUK persisted, and Parliament failed to amend the election law and reactivate the Kurdistan Election Commission, leading to the Federal Court’s decision on May 30, 2023, to annul the extension of the Kurdistan Parliament’s term. Subsequently, regarding the election law, several complaints were submitted to the Federal Court, and after many discussions and deliberations, on February 21, 2024, the Federal Court issued its decision on the complaints submitted by the PUK against the Speaker of the Kurdistan Parliament, the President of the Region, and the Prime Minister of the Region, requesting the court to rule on the unconstitutionality of several articles (1, 9, 15, 22, 36) of Law No. (1) of 1992, related to the structure of the Kurdistan Parliament, including the number of members, quota seats, the electoral system, voter registry, and candidacy list.

Some of the key points from the Federal Court’s decision are as follows:

Article 1 of the law specifies that the Kurdistan Parliament consists of 111 members. The complainant argued there is no legal basis for determining the number of seats, referring to Article (49) of the Iraqi Constitution, which states one seat per hundred thousand people. Consequently, the court ruled to reduce the number of seats to 100, without providing clear criteria. If it were based on the constitution, it should have been (61) seats because, according to the latest statistics from the Kurdistan Region’s statistics office, the population of the region is 6,103,274.

Article 9 of the law deals with changing the Kurdistan election map from a single constituency to multiple constituencies, which should not be less than four. This is a positive change as it emphasizes a more proportional representation system and reduces fraud opportunities.

Article 15 relates to reviewing and regulating the voter registry. This is a long-standing issue that should have been addressed by the parliament and the Kurdistan Regional Government. The responsibility lies with the Kurdistan Electoral and Referendum Commission, established in 2015, which has only conducted one referendum and one election, both using voter lists copied from Iraq’s electoral commission. Despite having resources and authority, the commission failed to produce a clean voter registry over the past nine years.

Article 22 addresses the legality of candidate lists and allows individual candidates while maintaining the gender quota. Political parties were unable to resolve this in the Kurdistan Parliament.

Article 36 addresses quota seats; the complainant requested distributing quota seats among governorates, but the court ruled to eliminate all 11 quota seats, which contradicts constitutional, legal, and reality principles, especially concerning Christian quotas.

The court also ruled Article 56(2), stating the parliament should not have the authority to make decisions on the destiny-related matters of the people of Kurdistan. This article was not initially part of the complaint, and it should mean the Kurdistan Parliament’s 2005 decision, which deemed the parliament the highest political and constitutional authority, should also be reconsidered.

The stance of political parties on the voter registry reflects a broader failure in political accountability and transparency, where political interests have overshadowed democratic principles and the rule of law.

The Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), which called for making the Parliament the highest authority, remained silent when the Federal Court overturned the second clause of Article 56 of Law No. 1 of 1992, reclaiming the status of the Kurdistan Parliament.

The Movement for Change (Gorran), the Kurdistan Islamic Union, the Justice Group, New Generation, and all those forces and parties that considered themselves opposition and demanded that the Parliament, by law, should be the highest authority representing the people of Kurdistan and should handle all destiny-related issues, were silent when the article was overturned and the Parliament’s status was reclaimed.

The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), which advocates nationalism and protecting the region’s status, also remained silent when the decision of the Federal Court diminished the Kurdistan Parliament’s authority and stripped it of its position as the highest authority representing the people of Kurdistan. The KDP, like other parties, went to court, the so-called “red court,” submitting complaints about some trivial issues unrelated to the Parliament's authority. Despite this, no stance or voice was heard from them on this matter.

We, as the Pay Organization, had previously declared in a statement that the court is not impartial and has made illegal and political decisions in some cases. Initially, it ruled in favor of holding the election, and later reversed itself to favor postponing the election, even contradicting its earlier rulings and suspending the election process based on the Prime Minister's agenda. According to Article 94 of the Constitution, the decisions of the Federal Court are binding and cannot be appealed or reviewed; they must be implemented without any option for annulment. This confirms that the Federal Court has never been impartial.

Although the KDP initially called the Federal Court the “red court of the Baath regime era,” on April 6, 2024, Prime Minister Masrour Barzani filed a lawsuit against the Independent High Electoral Commission, accusing it of violating the Iraqi Constitution and demanding the suspension of the Kurdistan Parliament elections until the complaint was resolved. Barzani claimed the commission’s division of the Kurdistan Region into four electoral districts violated the constitution and the Federal Court’s decisions because it based seat allocation on the number of voters, not the population of each district, contradicting Article 49 of the Iraqi Constitution.

In response, on May 7, 2024, the Federal Court issued a sudden decree halting the implementation of the second clause of Article 2 of the registration and approval system of the candidates’ list for the Kurdistan Parliament elections No. 7 of 2024. It stated, “The Parliament will consist of 100 seats distributed among these electoral districts: Erbil 34 seats, Sulaymaniyah 38 seats, Dohuk 25 seats, and Halabja 3 seats.”

The Federal Court in its statement, referring to the President of the court, announced that until the Prime Minister of the Kurdistan Region’s complaint is resolved, the execution of the decision is suspended to avoid severe consequences that may arise from its implementation in the future. The court ordered the commission to change the distribution of parliamentary seats in the Kurdistan Parliament, directly affecting the postponement of the election. Thus, the Federal Court halted the system of registering and approving the candidates’ list until the complaint was resolved.

Later, on May 21, 2024, the Federal Court rejected Masrour Barzani’s complaint against the election and halted the commission’s work. Barzani’s ultimate goal was to delay the elections, but the decision was overturned. Meanwhile, a separate ruling by the Judicial Authority of Iraq’s Independent High Electoral Commission restored five quota seats to the Kurdistan Parliament, allocating them within the 100-seat framework: 95 general seats and 5 seats for the minority groups in the Kurdistan Region, and the commission adhered to this decision. This ruling was based on a complaint filed by Yousef Yaqub Matta, head of the Assyrian Democratic Movement, demanding the return of minority rights. According to the ruling, the quota seats are distributed among the electoral districts as follows: two seats for Erbil, two seats for Sulaymaniyah, and one seat for Dohuk. As a result, the commission must announce the election postponement due to the lack of time to finalize the quota seat lists, register candidate names, and prepare the elections within the scheduled time frame.

Therefore, Nechirvan Barzani, the President of the Kurdistan Region, is once again compelled to annul the previous decrees, similar to past decrees, and issue a fifth decree setting a new date for the sixth parliamentary election, which is expected to be in September or October this year. However, even in this new timeframe, which has not yet been finalized, the election may still be postponed, potentially requiring the President to issue yet another decree!

Conclusion:

The political leadership of Kurdistan has never aligned itself with the culture of democracy, elections, and the transfer of power.

None of the electoral processes in the region have been conducted within their scheduled timeframe, and the political parties have not adhered to the law.

The parliamentary experience in the region has regressed strategically due to the actions of the parties, going backward from term to term.

The dominant political forces are not willing to relinquish power and are keen to stay in control through force, money, and foreign assistance.

Opposition forces have been short-sighted, reactive, and lacked strategic vision, merely taking operational steps rather than strategic ones.

The voter registry has always been a tool for the political parties to justify election delays.

Each time, the main parties (KDP and PUK) have used different excuses to manipulate the election process.

In most elections, the two main parties have engaged in fraud to gain the most seats.

International pressure has only extended the current power structure under the guise of protecting their own interests.

Recommendations:

A comprehensive political agreement among the political forces in Kurdistan should be reached to set an appropriate date for the elections as soon as possible.

A robust voter registry should be prepared during this period, and fake, duplicate, and deceased names should be removed.

The quota seat issue should be resolved in a way that serves the interests of the minority groups, not the authorities' interests.

Political parties should nominate strong candidates for Parliament, avoiding populism and prioritizing merit.

There should be a return of authority and decision-making power to Parliament, reinstating it as the highest political and legal authority of the Kurdish people, particularly in matters of destiny.

A unified agreement should be made on the future of the Kurdistan Election and Referendum Commission. If the political parties trust this commission, after the sixth term elections, the first task of Parliament should be to reorganize and reactivate the commission so that future elections are not fraught with issues. If they do not trust the commission and see it as weak, they should allow the Iraqi Electoral Commission to manage the elections, avoiding wasting public funds.

Link to the Article:

https://zedpress.krd/political/12005/